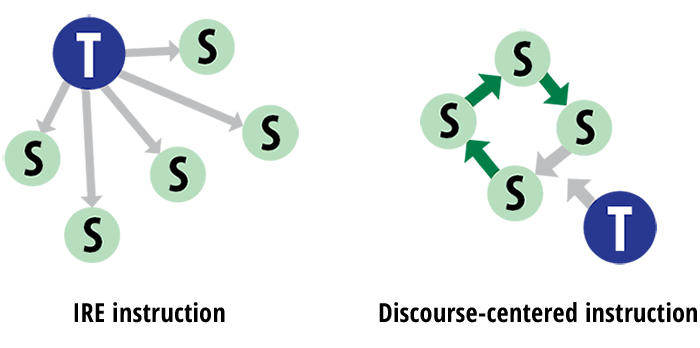

Helping students analyze complex ideas collaboratively often calls for some changes in classroom interaction patterns. Consider the two patterns shown here.

Which one gives students more responsibility for thinking deeply and collaboratively? Which one provides more opportunities for students to use and strengthen their language?

The model on the left, often described as IRE for teacher Inquires, student Responds, teacher Evaluates (Schegloff, 2007), offers few opportunities for students to say more than one or two words, rather than to explain their rationale. Additionally, only a small number of students get to speak, and many ELs don’t volunteer responses in such a high-pressure, quick-response situation. The IRE pattern offers teachers little useful information. Knowing that a student’s answer is right or wrong doesn’t reveal much about the student’s reasoning.

The reasoning-centered, discourse-focused model on the right offers multiple opportunities:

Quotation: “Essentially all of the science and engineering practices require student discourse to be a central element of classroom activity, and, properly managed by the teacher, such discourse includes all students and pushes every student to refine and extend language abilities.”

(Quinn, 2015, p. 14).

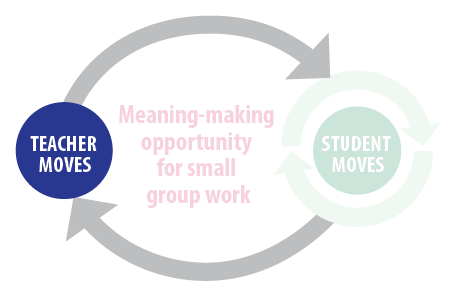

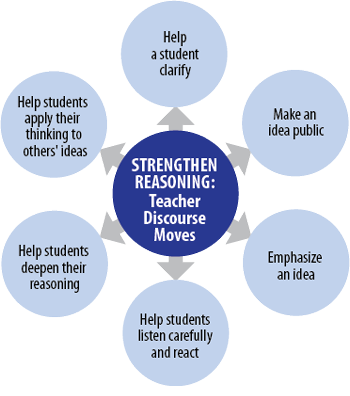

The move to discourse-centered instruction is a powerful one, both for students and teachers, but it represents a shift for teachers who have been trained in the IRE model. To support teachers in making this shift, we created a simple tool to show six ‘moves’ that a teacher can make to keep the focus on student ideas.

This graphic shows the six Teacher Moves: several ways to probe and strengthen students’ reasoning, to keep their ideas moving forward, and to keep students talking to one another. Teachers in our project found this simple graphic to be a helpful reminder of the strategies they could use to avoid the familiar ‘teacher as expert’ mode and keep the responsibility for the idea in the hands of the students. The complete version of these Teacher Moves on the Resource page gives examples of ways to phrase these moves. Most teachers found the examples helpful initially to help them learn the Teacher Moves, and later simply enlarged and laminated the small graphic and kept it nearby as a reminder.

A few elements of the Teacher Moves deserve a bit of highlighting. Listed under Help a student clarify is the hint to allow 20-30 seconds of wait time to elapse before giving a second prompt, and to allow the same amount of time after a student has made a remark. Thinking is hard and takes time, and putting complex ideas into words is not easy. We’re asking students to “think out loud”, and ideas rarely come out fully developed or clearly articulated the first time, even for experienced speakers. Waiting patiently for a student to say more often leads her to continue to explore her idea aloud or to state it more clearly, and this gives others additional opportunities to follow along and think it through with her.

Another important strategy listed under Make an idea public and Help students apply their thinking to others’ ideas is the reminder, when revoicing a student’s idea, to always ask the student if you’ve expressed the idea correctly. After all, it is the student’s idea, and we want to make sure our revoicing (perhaps to clarify or to model simpler or more precise language) doesn’t change the idea. We need to build this same habit among our students, as well, so that they respect the integrity of one another’s ideas. We’ve observed remarkable examples of ELs persisting in clarifying their ideas aloud in response to this humble question from a teacher: “Did I say that correctly? Try it again, please. I’ll try to do a better job of understanding.”

“I don’t have to wait for the test to find out what my students know. I can listen to them explain their thinking, and I can steer them in helpful directions.”

a fourth grade science teacher

teacher MOVES IN SCIENCE

Teacher Moves in Math